Image

Source

Parry, Nigel. 2005. “Well-known UK graffiti artist Banksy hacks the Wall.” Electronic Intifada. September 2, 2005. https://electronicintifada.net/content/well-known-uk-graffiti-artist-banksy-hacks-wall/5733.

Language

English

Contributor(s)

English

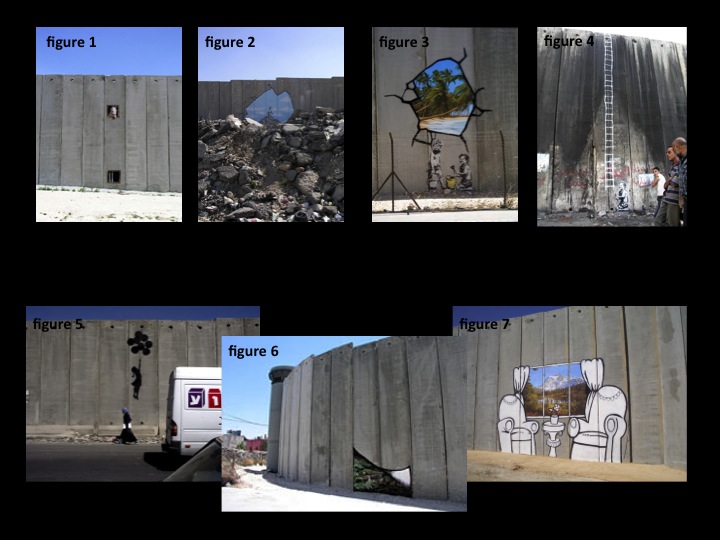

Substantive Caption: The seven images I have organized on this single slide are photographs from the occupied Palestinian territory of the West Bank. The photographs are of graffiti art painted on to the separation barrier, jithaar al ‘aazil, Israel is constructing on Palestinian land in the West Bank. In the article accompanying the images, Nigel Parry looks at the work of Banksy as a response to self-proclaimed “design critic” Nathan Edelson. In 2003, Parry, cofounder of the Electronic Intifada, received an email from Edelson requesting images of the barrier being built by Israel on Palestinian land. In his email, Edelson explained he was writing an article on the barrier, “the premise of my article is that one can argue about the desirability of a wall, and certainly where it runs, but if it is going to be built it should not be an aesthetic monstrosity” (2005, Edelson qtd. in Parry). As a result of this potentially “aesthetic monstrosity” Parry highlights the work of Banksy as a call to action against the fundamentally illegal wall itself. Rather than making beautiful this toxic site of monstrosity, Parry explains the significance of Banksy’s artwork as a critique of the wall entirely. Parry writes, “Banksy’s the kind of guy who prefers to draw a 20 foot high arrow pointing at the ugliness to encourage us to ask why the hell it’s there in the first place” (2005, Parry). The title of Parry’s article is “Well-known UK graffiti artist Banksy hacks the wall.”

Descriptive Statement: I chose to highlight the images of Banksy’s art because:

While Banksy may have set-off alarms earlier this year when a framed piece of his artwork auctioned off at London’s Sotheby proceeded to self-shred seconds after being purchased, his graffiti work has been giving new life to the slabs of concrete being erected on Palestinian land in the West Bank since the early 2000s. Operating under anonymity, Banksy’s graffiti paintings on the “separation barrier” offer, figuratively and literally, new ways of seeing and thus being for Palestinians.

Banksy’s canvas for a series titled the “Wall Project” was a concrete structure. This “wall” is estimated to reach approximately 403 miles (605 kilometers) in length when completed and stands at 25 feet high (8 meters). According to B’tselem, an Israeli human rights organization in the West Bank, the barrier denies approximately 150 Palestinian communities from their farmlands and pasture lands (“The Separation Barrier,” nd). As a result, Israel has effectively blocked thousands of Palestinians from freely accessing and cultivating their land, producing a condition of economic and environmental occupation predicated on Israel usurping Palestinian land. According to data presented by B’tselem and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the occupied Palestinian territories (OCHA-oPt), Israel has installed 84 gates in the completed sections of the Apartheid wall, however only a fraction are in operation. In 2016 for example, only nine of these gates were opened daily; ten were opened a few days a week and during the olive harvest season; and 65 gates were only opened for the olive harvest (ibid). Effectively, the “wall” has produced a condition of continual degeneration. Palestinian communities, farmlands, and sources of sustenance have been fractured by the concrete cutting through their land. These damaging effects can be understood as a form of toxicity rooted in degeneration, where all aspects of life are splintered off, denied any semblance of wholeness.

The wall, as a method of control and isolation, has dualistic function in Banksy art: it is both canvas and prop. In the seven examples I have highlighted here, the viewer is forced to contend with the uncomfortable realities impeding Palestinian social, cultural, and economic worlds. The wall acts as the citational index from which Banksy’s images come to life. As Parry aptly notes, “familiar images...are given a dark twist designed to wake observers up from the 9 to 5 rat race” (2005, Parry). Images of farm animals, children, beachscapes, blue skies, balloons, living rooms, scenic panoramas are all confronted with the reality of inadmissibility imposed onto them by the separation barrier. The viewer is forced to take pause and perhaps tilt their head from side to side in focused observation studying closely the images as if to make sense of them. Simply put, however, they do not make sense. The horse (image 1), whose body appears to be stretched like a rubber band, peers its head out through the small square opening near the top of the barrier while its hooves are visible through a square window towards the bottom of the barrier- a distance that is factually impossible, yet exists, much like the wall itself. In image 2, the viewer sees two obstructions: the wall and the pile of rubble, rocks, and trash immediately in front of the barrier. Almost as if emerging out from the rubble is a child atop a sand castle, with a small yellow pale in his right hand. In a sea of grey, from the wall and rubble beneath it, the child emerges perched on a sand castle in the middle of a bright blue sky. Here Banksy does not alter the geography to make way for his work. Rather, all toxic elements become part of the art installation. The trash and rubble immediately in front of his painting are worked into the art piece. In an act of continuity, the child in image 2 is present in image 3, this time with a friend, also carrying a his sand toys. Their little bodies are situated beneath painted lines which give the effect of a break in the wall, revealing a beautiful sandy beach destination, with palm trees, and blue skies. According to Parry, “much of the art he produced on the Wall visually subverts and draws attention to its nature as a barrier by incorporating images of escape” (2005, Parry). Windows, new landscapes, ways out, are all techniques used by Banksy to reveal new worlds to those imprisoned by the barrier. Take for example Qalqilya, a city in the north of the West Bank. Qalqilya is entirely bottle capped by the separation barrier, with one main entrance in and out of the city. According to Environmental Justice Atlas, an online resource documenting and archiving environmental (in)justice issues around the world, the virtual sequestering of Qalqilya has led to a loss in biodiversity (wildlife and agro-diversity), contributed to food insecurity as a result of crop damage, aesthetic and land degradation, soil erosion, waste overflow, deforestation and loss of vegetation cover, water pollution, and decreased water supply (Gamero, 2017 for EJAtlas). The barrier thus functions to erode the natural resources and life forms in its path, producing topographies of toxicity. These topographies become the canvas sites for Banksy’s work where the sheer violence of the barrier is called into question and recast in new ways.

Images 4 and 5, for example, offer exit strategies. In both paintings, Banksy uses children to signify the possibilities of new ways of being and existing. At the borderland- that material and discursive site where real borders and barriers are confronted with affect and experience- we see a little girl being carried away by balloons (image 4) and a little boy at the foot of a tall ladder (image 5) extending the length of the wall- both making their exits, beyond the obstructions of the barrier. In both instances, the children carry the possibility of breaking down the border plaguing their existence. Banksy’s installations on the wall “invoke a virtual reality that underlines the negation of the humanity that the barrier represents” (Parry, 2005).

Sources:

Parry, Nigel. 2005. “Well-known UK graffiti artist Banksy hacks the Wall.” Electronic Intifada. September 2, 2005. https://electronicintifada.net/content/well-known-uk-graffiti-artist-banksy-hacks-wall/5733.

2017. “The Separation Barrier.” B’tselem. November 11, 2017. https://www.btselem.org/separation_barrier

Gamero, Jesus Marcos. 2017. “Orchards affected by the Annexation Wall surrounding Qalqilya, West Bank.” Environmental Justice Atlas. March 31, 2017. https://ejatlas.org/conflict/impact-of-the-wall-surrounding-the-city-of-qalqilya-affecting-orchards